How Do They Grow Up So Fast?

|

| The future president of Mars at the zoo, age 4 |

I dropped my oldest son off at college last weekend. All week, I had been busy planning for a semester start of my own,

putting the final touches on my English Composition fall syllabus for first-year

students, a class I love to teach because it opens students' eyes to the

possibilities of writing, to the power of communication. And then, my phone

buzzed with a text message from my son: “It is really hard to say goodbye to

everyone.”

I remember that feeling.

Parenting is hard. This oldest child of mine, like all

oldest children, was an experiment, a very wanted child, but also an

unknown. I was in graduate school when I

learned that I was pregnant. I thought I would just deliver my first baby over

spring break and return immediately to school a week later. He was born just

six hours after I turned in my grades for the History of Rome section I taught

as a UCLA teaching assistant, just six days after I successfully defended my

academic work in comprehensive written examinations, struggling with

Braxton-Hicks contractions as I labored (figuratively and literally) to translate difficult

Greek passages and apply them to theoretical contexts.

For me, motherhood changed everything. Puer natus est, the Roman poet Virgil wrote in his

Fourth Eclogue

about the birth of Augustus Caesar, destined to be the first Emperor of Rome.

“A child is born.” Is there a pronouncement more existentially profound?

My first child was obsessed with the space shuttle

before he was two. He built rockets, first from Legos, then with real rocket

fuel he cooked in my kitchen with sugar and cat litter. From an early age, he

studied everything he could find about the Titanic, informing me as a

preschooler that he would only watch documentary films, because “fiction is not

true” (I beg to differ: sometimes it seems to me that fiction is more true than

so-called facts).

When he was four, he swallowed a quarter because he wanted

to know what it tasted like and earned his first (and last) ambulance ride.

When he was 14, he broke both arms in a frightening parkour accident: My first and

most urgent question to the emergency room doctor: “How is he going to wipe his

own bum?” His younger brother had been in the same emergency room just two

weeks earlier, transported by ambulance after a violent behavioral episode

associated with mental illness.

I did not follow the plan and return to graduate school the

week after my oldest son was born. I stayed home for 12 years to raise him and

his 3 siblings. Nor did I plan on his father divorcing me. But when that

happened, I gradually picked up the pieces and moved on. A few years later, I

started an online doctoral program in Organizational Leadership (my kids describe what I study as “Advanced Manipulation Techniques”), and

now, as my first son prepares to start his first year of college, I am

preparing to defend my own doctoral dissertation proposal on mental health

advocacy and leadership. We put many of our personal goals on hold when we become parents, but I'm glad I've returned to mine.

The family jokes that my oldest son is the future president of Mars.

It might not turn out to be a joke. He certainly has the drive, the talent, the

ambition.

But in so many ways, I feel like I have failed him.

His younger brother’s struggles with then-undiagnosed mental

illness, coupled with a difficult divorce, defined our family in ways that I

wish, as a writer, I could revise. Mental illness affects the whole family, and

I think the sibling experience has not yet been adequately chronicled or

supported.

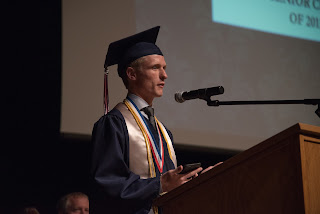

|

| And at age 18 as commencement speaker at his high school graduation. |

Still, as Dante said, we are a part of all we have met. My oldest son has met and conquered many challenges in his formative years, and

I know that he will continue to achieve at a high level as he begins his

college experience.

For my part, as I loaded up the Suzuki with boxes of his clothes

and books and Star Trek models, I just wanted him to have fun. To be safe. And to

learn to be happy.

Right before I left him to begin his new phase of life, I gave my son a journal inscribed with this message:

“I’m not sure whether this means I’m a good parent or a bad parent, but I am really ready for this day—the day I officially get to hand your future off to you. I’ve watched you grow up to be brave, capable, and incredibly talented. Now is the time to be curious, to explore the world of ideas. I went to a relatively crappy college in a crappier town than your school, and I ended up loving every minute of it. The books I read in college are still my favorite books. The friends I made are still close. But most important, college made me the person I am today. Be curious.

P.S. Keep a journal! You’ll laugh really hard at what you wrote when you’re my age.”

As I turned to walk away, my cheeks were wet with tears. I blamed the moisture on the smoky air from all the Idaho wildfires. But my son and I both knew differently. His future is now his.