For mothers of teenagers like me, news about a school shooting never gets any easier. We experience the same dread, the same despair, the same fear that someone will attack our children’s school. In between mass shootings, we drill our children on what they would do. We check on their social media accounts. We try to pretend that there’s some sense of safety in a world that always seems full of random, unpredictable violence.

I’m the mom CNN used to call whenever there was a school shooting. And today, one day after 17 children who are the same age as mine did not come home from school because of another mass shooting, I’m angry. Predictably, politicians have tweeted meaningless “thoughts and prayers.” Also predictably, some Republicans have tried to shift the blame for the latest massacre to the isolated actions of a “mentally disturbed individual.”

After the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting five years ago, I shared my story of parenting a child with violent behavioral symptoms of a then-undiagnosed mental illness in a viral essay entitled “I Am Adam Lanza’s Mother.” In that essay, I wrote, “It’s easy to talk about guns. But it’s time to talk about mental illness.”

Now, I’m concerned that we are having the same blame and shame conversation without any meaningful action, as this viral Facebook post shows.

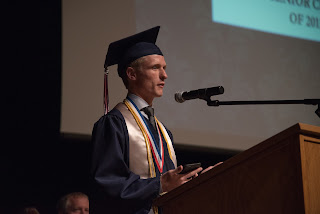

Today, with the correct diagnosis (bipolar disorder) and treatment that works, my son Eric lives in recovery. In 2016, he even gave a TEDx Boise talk about his experiences. Eric is a normal high school senior who, like many of the Parkland, Florida students, is planning for college next fall.

Today, I feel that blaming mental illness for an epidemic of violence in the wake of so many mass shootings has become a meaningless trope. If politicians and the National Rifle Association really believe that mental illness causes mass shootings, it’s time to put their money where their mouth is. Here are a few suggestions:

1. Provide funding for research into treatments and cures, perhaps by donating the millions of dollars that the National Rifle Association gives to their campaigns.

2. Continue to support parity for mental and physical health, currently required by the ACA but already under threat in my own state.

3. Stop blaming children and their parents for the appalling lack of community mental health services and supports.

4. Understand that when treated, people who have mental illness are no more likely to be violent than anyone else. Treatment works and recovery is possible.

5. Adopt reasonable and bipartisan gun control measures that focus on suicide prevention, since more than 60% of deaths by gun violence in the U.S. are completed suicides, a tragedy that disproportionately affects the brave men and women who serve in our military.

Most people can agree that universal background checks and allowing the government to track gun violence statistics (currently prohibited by federal law) are good first steps to better understanding and controlling our nation's clear gun problem.

To be transparent, I live in Idaho, a gun-loving state. I grew up in a family that hunted, and my brothers taught shooting sports at Boy Scout camp. I have enjoyed shooting sports in the past. While I do not personally have guns in my home because of my son’s illness, I know many responsible gun owners, some of whom live in recovery.

Yes, it’s true: people who have mental illness can be responsible gun owners, which is why mental health advocacy organizations including the National Alliance on Mental Illness believe that “Federal and state gun reporting laws should be based on these identified traits, not mental illness.”

People who are in treatment for mental illness and are compliant with treatment should not be treated any differently than anyone else. To focus on mental illness as the sole cause of mass shootings is a clear example of the pervasive discrimination and fear in our society. In fact, while it’s true that at least one-third of mass shooters seem to have had an untreated mental illness, a more common predictor of this kind of violence is a history of animal abuse or domestic violence, as is the case with the Florida shooter. Both of these deplorable behaviors are actual crimes, and both of them should require immediate intervention including loss of gun rights.

But mental illness is not—and should not be—a crime.

It’s time to act. Build the community mental health treatment centers. Fund research into cures. And most importantly, stop blaming by association the millions of good people who live in recovery for the violent actions of a few.